That the Southern Diaspora helped African Americans in their historic struggle for civil rights is widely understood. But how it did so has never been carefully explained. Indeed since the 1960s scholars have written about black political development in ways that undervalue the role of the northern Black Metropolises. Partly it is because the southern civil rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s loom so large that there is a tendency to treat everything that came before as prologue. Partly it is because few of the historians and political scientists who have written on the subject have cared enough about political geography. The result is an oddly inconsistent narrative that always includes the point that the black diaspora brought with it voting rights and increased political visibility but fails to follow up in any consistent manner.

This chapter does so, making the point that the Black Metropolises provided the base for a sequence of extremely important political developments that were not just prelude but precondition to the southern civil rights breakthroughs of the 1960s. There was a particular regional dynamic behind the twentieth century drive for rights and equality, an almost Archimedean logic: African Americans had to leave the South in order to gain the leverage needed to lift it and the rest of the nation out of Jim Crow segregation....

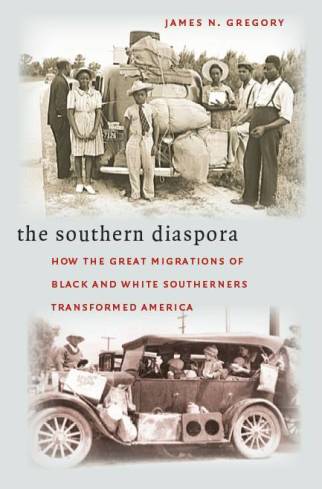

excerpts from Ch 7 "Leveraging Civil Rights" -- The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America (University of North Carolina Press, 2005) |

- - - -

TOOLS OF BLACK POLITICS

African Americans developed political capacities in the North that were not available in the South. The right to vote is obvious. As Thomas Brooks once put it, migration out of the South was a move “almost literally, from no voting to voting.” But that by itself explains little. Voting does not automatically translate into influence, especially for social groups that are outnumbered and socially isolated. It was not the vote itself that would prove important; it was the way it was used and the context in which it was used. One of the most important forms of power that African Americans would develop in the North was the ability to marshal votes in contexts of competitive politics. Because the spaces they occupied offered a number of balance of power opportunities, northern black voting became highly productive at certain junctures.

Voting was only one of the tools that became available in the North. The ability to build productive alliances was another. Here too context was key. The diaspora was fortuitously aimed at a select set of cities that were uniquely situated as centers of American cultural and political influence and that had resources available nowhere else. Over time black communities developed political relationships in those cities that gave them access to various forms of influence. Evolving ties to the urban intelligentsia, to socialists and communists, to Jewish communities, to organized labor, and through them to the northern Democratic Party would provide openings in turn for influencing government practice and policy at various levels.

Protest was the third new tool that the North offered. The ability to raise voices and move into the streets, to be visible, demanding, militant, and at times violent was another political device that belonged to the big cities. Pioneered by organized labor, street tactics had become part of northern urban political culture by the time of the Great Migration and proved an essential weapon in the arsenal of black political practice. The threat of disruption would at various junctures compensate for the limitations of the other levers--strategic voting and alliance building--forcing some of the allies to take black needs and demands more seriously than they otherwise intended.

Sectionalism was the fourth weapon in the arsenal of northern black politics. One of the keys to building alliances and gaining white support at critical junctures was the notion that the white South was primarily to blame for racial injustice and that the South should be the chief focus for both rhetorical and legislative struggles. This was a position that the NAACP adopted when it made lynching its high profile issue in the 1920s but it went back much further, woven into the political culture of the Republican party, a sectional solidarity that white northerners and black northerners had shared since the civil war. All the way up to the mid 1960s, this eyes-on-the-South agreement served in complicated ways to help African Americans build influence and leverage....

- - - -

It was once well understood that the modern civil rights movement began in the 1940s and that it took shape in the cities of the North. “When, in 1990 perhaps or the year 2000, men come to search for the truly decisive epoch in American race relations,” Lerone Bennett, Jr. wrote in his 1965 book Confrontation: Black and White “it seems likely that they will seize on the decade of the forties.” The Mississippi-born, Chicago-based contributing editor of Ebony magazine understood that the great events that had unfolded after 1954—the federal court decisions that had opened up the battle for school desegregation, the electrifying confrontations in the South and the mediagenic movement that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. led, the congressional alliance that had, months before his book appeared, passed the historic 1964 Civil Rights Act –that all that rested upon a foundation that had been built in the Black Metropolises in the 1940s.

Bennett, however, was wrong about the historiography of 1990. By that year the story of the 1940s Civil Rights movement had almost been lost as historians focused on the South and ignored what preceded it....

excerpts from Ch

7 "Leveraging Civil Rights"

How to cite and copyright information | About project | Contact James Gregory

Follow the Project and receive updates on Facebook Facebook